Media Interviews and Articles

This section includes interviews I’ve given magazines and newspapers, some nationals and others obscure, and a few articles I have written about research for my thrillers in some interesting and often dangerous places.

In part it will answer a lot of those questions that all us readers love to ask – yes, I’m a reader, too! For example “where do you get your ideas from?“

Free Choice

Interview with author Terence Strong by Smoking Magazine.

Wimps of War

Account of author’s research with Royal Marines in Norway.

Bombing out in the Andes.

Account of author’s research in South America.

Walk on the Dark Side

Account of author’s research in Northern Ireland.

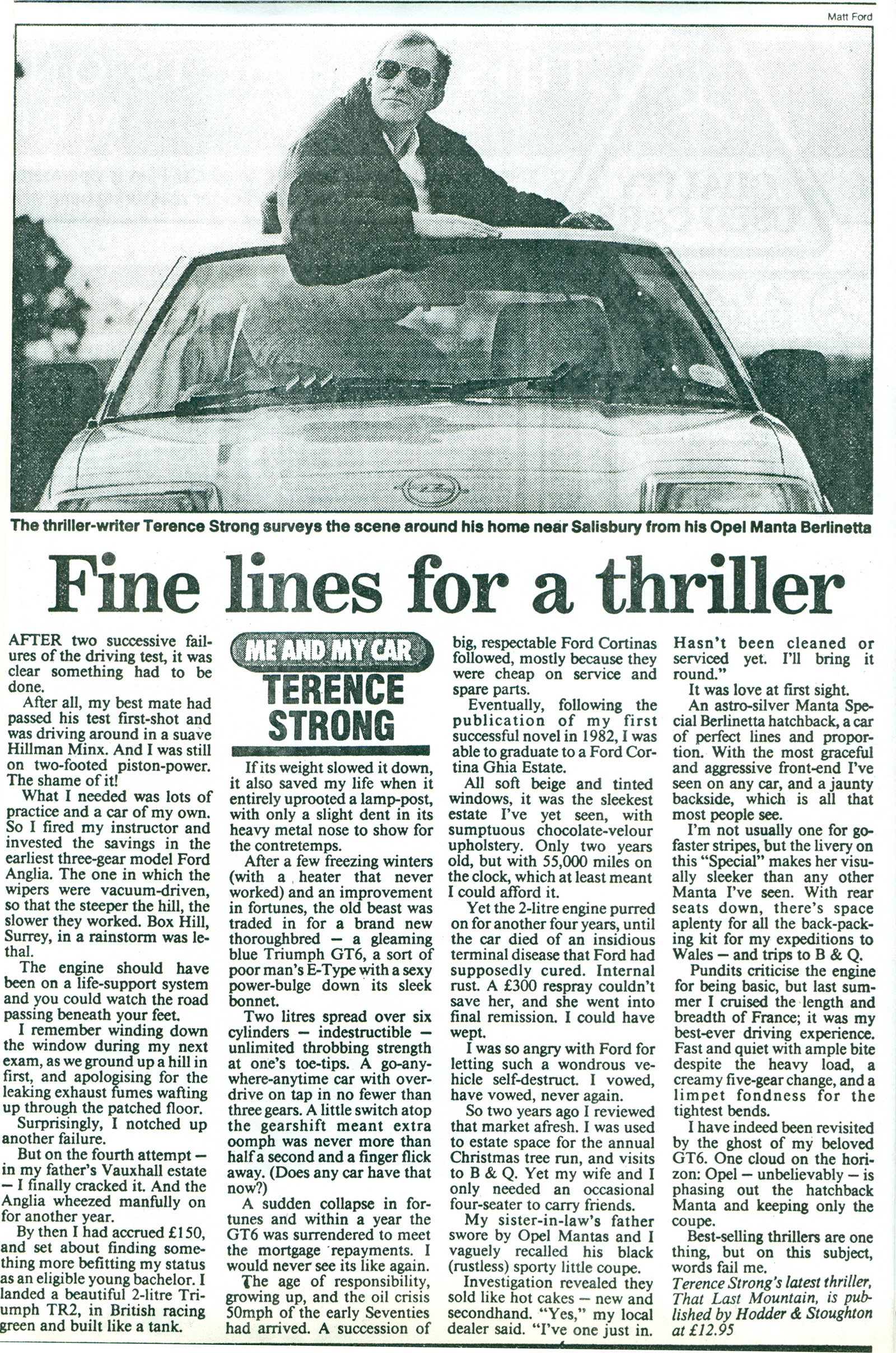

Me and My Car

Article in the Sunday Times.

A DAY IN MY LIFE by Terence Strong

I suppose starting the day with unusual breakfasts in unusual parts of the world is one of the more dubious perks of thriller writing – or at least their research. Scoffing a disgusting mix of porridge made with cocoa twelve feet under the Arctic snow with Royal Marine bootnecks was one of the more memorable starts to the day.

Buying hot ready-made maize porridge from a remote West African village market was an infinitely more enjoyable experience. Also better than the acquired taste of santafereno – which is bread and cheese dunked in an accompanying cup of hot chocolate – in the remote narco and guerrilla badlands of Colombia.

There is definitely much more to be said for breaking fast over coffee and dates with Bedu tribesmen in the Arabian Desert. But when the roaming and adventures stop and the hard work starts, breakfast is more prosaic. Just some un-sugared cereal like Shredded Wheat with skimmed milk and a mug of sweet black coffee. This can be at any time from 7.30 to 10 am.

The first chore of the day (and a major effort at weekends!) is to scour the quality papers for snippets to be filed for future use. I keep press-cutting files on subjects and regions of the world I think my readers might be interested in. When I decided to write about China, I opened up my Far East file and lo! – all the facts I wanted were ready and waiting. It made all the hard work worthwhile. As a lad, I was able to travel the world within the Biggles books and I like to think I’m doing something similar for grownups.

Taking them to places and giving them experiences they can’t have in a 9 to 5 job. Creative work starts at 10.30, when I can’t put it off any longer, facing that blank page. Like many writers I have silly idiosyncracies. For instance, always using a juicy black Ball Pentel that allows the words to flow effortlessly onto the paper of an 80 page feint-ruled Silvine Refill Pad. And a superstition – only buy one pad at a time; to get more is to tempt fate. You may never get to use them.

For the first time I wrote most of Deadwater Deep on the word-processor. As I’ve always suspected, there’s a temptation to keep going back to tart up what you’ve just written rather than drive on with the story. But I did it this way to meet the deadline, and it worked because the main re-write took one instead of the usual three months! But I hated it, and hope to return to the handwritten first draft next time.

It’s fascinating to see how the handwriting changes from scene to scene. Small, neat and measured for those careful descriptive passages and telling dialogue. Compare that to when ‘our hero’ is scaling a cliff or battling with sharks, or the SAS is busting a siege – an illegible scrawl as I race down the page in a fast upbeat tempo that can leave me feeling as drained as the character himself.

A thousand words – or four pages – and a break for lunch. In theory, this endless routine will produce some 160,000 words in six months or so. But in reality it takes longer. One’s forever looking up and checking details or writing stuff that has to be cut later, but it is the thinking process of getting the story to its next destination. Thankfully this annual slog up the new mountain is interspersed with occasional trips to ‘the smoke’. I’m a London boy, born and bred and, despite loving the country, I yearn for a regular ‘fix’ of city life.

In former times, lunch might have been at L’Escargot or Des Amis du Vin with Carolyn Caughey, my former editor at Hodder & Stoughton. Since then lunches have been with the charming young whizz kid editor (he’ll hate that) Tom Weldon who rebuilt Heinemann, and who was part inspiration for the Boy Lansdowne – a Secret Service executive in Deadwater Deep.

At other times, of course, it’s lunch with ‘yourself – but not alone’. In law, of course, your agent is you. Like you, agents are witty (or pretty), efficient, and agree with every word you say! Great companions.

Other lunches – more usually at my expense – are with experts in their field whose brains I need to pick, They might be ex-special forces, police or customs officers, hostage negotiators, bodyguards, criminals, journalists, diplomats, representatives of terrorists, mercenaries, assassins … the list is as endless as it is fascinating.

Without these kind helpers giving so freely of their time and knowledge the modern thriller, with its demand for factual accuracy, would simply not be possible.

Moreover many undertake the task of reading the second (typed) draft thrust upon them. For Deadwater Deep, nine kind souls read through all or part of the manuscript, including two marine engineers who virtually created a totally feasible state-of-the-art stealth submarine for me.

On a workday afternoon, I aim to turnout another thousand words. If my concentration starts to flag, I might draft a reply to any readers’ letters I’ve received. I never realised how important it was to write letters to authors saying what you think of their latest work.

You sit closeted in your ivory tower, hardly believing that hundreds of thousands of faceless commuters are actually buying and reading – let alone enjoying – the words you’ve written. How wonderful to hear the tales of burnt dinners and home stations missed because they ‘couldn’t put it down’.

It makes it all worthwhile.

It’s pens down for the dumbed-down ITN News at 5.40 – to see if it’s worth watching Channel 4 News later – followed by half-an-hour’s work-out on the multi-gym.

Then it’s a TV supper, which gets increasingly difficult nowadays. Apart from some documentaries, it comes to something when the best ‘popular programmes’ are Changing Rooms, Ground Force and, of course, Have I Got News For You.

I took up cookery some eight years ago and love it. If I sometimes prepare an – inevitably over-elaborate – meal; it’s so late and badly-timed that we miss the programme we’d planned to see and, after a bottle of red wine, can never seem to find it again on the video tape.

Most of my reading is non-fiction for research; a Graham Greene is a rare and special treat, usually reserved for holidays. Among my other choices would be Gordon Stevens, Bryan Forbes or Jack Curtis, or travel writer Stanley Stewart.

Of all the activities I’ve taken up as part of research (self-defence, scuba diving and rock-climbing) skiing and backpacking remain the favourites.

Bed is rarely before 12.30, but there’s no insomnia here. Creepy-crawlies, icy winds, driving rain, howling gales – I sleep blissfully through the lot.’

Free Choice Magazine Interview

Author Terence Strong is a former member of the freedom-to-smoke organisation FOREST. Its magazine Free Choice went to interview him on the publication of his twelfth book, Deadwater Deep.

AN INTERVIEW IN THE LIFE OF TERENCE STRONG

Terence Strong has two reasons to be grateful to the Internet. Firstly, it has saved him an inordinate amount of time and expense researching his latest book – set in China.

Secondly, it has spared him a grueling long haul flight to the Far East journey in which he would have had to abstain from smoking.

“Normally I research my books on the ground,” says the crime thriller writer. “But the plot was co-developed by a CIA friend of mine via email. It meant I could write it using the internet without having to go to China and suffer a no-smoking flight.” Terence is a passionate FOREST member. We’re not revealing what (or how many) he smokes because … “Whether I smoke or not is irrelevant. The reason I support FOREST is I’m a Libertarian.”

Among his credits are the best-selling Whisper Who Dares, The Tick Tock Man, The Fifth Hostage and That Last Mountain.

For those who don’t snuggle up to him in bed every night Terence is a special services scribe. He modestly lists – but only after persistent probing – the SAS, the ‘old’ IRA and British and American intelligence as among his many contacts.

In his early school days Terence was no academic genius – he failed his 11 Plus. But it didn’t stop him penning his first novel at just 16. “The publisher demanded I halve it” he recalls with a chuckle before revealing he tucked it away for several years before re-submitting it. He then suffered a mild form of writer’s block – not getting round to penning another book for eight more years.

But since then smoke has been pouring out of his pen – and terminal. On average he produces a title every year, describing the feat like “climbing a mountain”. His latest book – at the other end of the geological spectrum – is called Deadwater Deep.

Terence’s passion about smokers’ rights runs deep. He signed up more than five years ago and says: “I’m a great believer in the courtesy of choice. I believe the world is a big enough place for all of us.” Terence is fervent on the subject of discrimination against smokers in the workplace, on planes and on trains. He is not so ardent about bus bans (because journeys are shorter) and is even in favour of both designated no smoking and smoking areas in pubs, where practicable.

One issue he is totally passionate about are central bans. “It’s not a government’s position to tell everyone what they should or should not do,” he says.

“It’s their duty to inform honestly about various health risks and to reasonably encourage or discourage. Then it’s up to the public to make up their own minds.”

Whatever this or future administrations have in store, though, you can be rest assured it won’t affect the central characters in Terence’s novels. He usually makes them smokers, explaining: “It’s a subliminal thing. I’m not promoting them smoking, but I’m saying they are human beings and therefore they can be heroes or heroines. The fact they smoke doesn’t make them bad people.”

The Wimps of War

Research for That Last Mountain by Terence Strong.

First published in ‘News at 2’ magazine (Welbeck PR)

HQ 42 Commando, Royal Marines, Norway

The go-anywhere BV snowcat

We ‘civvies’ had arrived at the bleak, rain-swept transit camp the night before. Not surprisingly, we gravitated towards the scent of alcohol. If you hadn’t noticed, ‘Fleet Street’ men and homing pigeons have a lot in common. The Pegasus Club was where we came to roost – until they pulled the shutters down.

Morning screamed at us at 0430 hrs in the shape of a Nazi wardress, whose job it is to make sure that no one staying in the transit services ‘hotel’ ever misses their flight.

With luggage and hangovers smartly packed, we were delivered to the camp restaurant for breakfast. The sight of a dozen poached eggs swimming in a vat of water didn’t help. I’d seen two only fifteen minutes earlier in my shaving mirror. We settled for a plate of grease cunningly camouflaged as sausage egg and chips.

Once in the cavernous, cold and noisy hold of the huge four-engine Hercules C30 transport aircraft, the RAF fill you with orange juice and don’t tell anyone about the primitive urinal facility near the rear ramp. We didn’t twig that until the return flight.

As the doors opened, the Norwegian air hit us like a sledgehammer. It didn’t mess about. Minus twenty. Like standing over an open freezer in Asda. An intense, penetrating cold that stung the skin.

I was dumped on the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Training Cadre – a tough eccentric group who train Marines, Army, SAS and SBS to be ‘mountain leaders’. They crack ice to go swimming, climb Everest, things like that.There’s not much to see – everyone’s up above the treeline ‘on the course’ for days and nights on end. Those who are left administer, drink and fraternise with local Noggy girls in huts up in the hills. They’ve got it all organised. Like their mess bar, developed over the last 3 years since they’ve been billeted at this picturesque holiday chalet complex, the bar is decorated in tasteful white drapes of camo netting making it the Stringfellows of the North.

The bar closed at 4.30 am. And my drinking companions celebrated the dawn with a 17 km mountain run to ‘clear the head’. I was glad to transfer to the cushy life of L Company at Hendsaeter.

Lovely man, Captain Newing. A gent. Greeted me with a warm smile and a half pint of Scotch. He was most apologetic about the cramped conditions and the alternative accommodation. Just a short ride away. By BV snowcat. Up to 6,000 ft. Across a thousand metres of snowdrift. To an 18″ rabbit hole at its base, which after 30 slippery feet, blossoms out into a wondrous man-made cave.

We slept together that night.

Buster and me. Sharing the double-bed of pack ice with a ceiling of snow 12″ above our noses. swapping yarns in the glow of the survival candle. When that goes out you know the air’s gone, and so are you.

But it was a cosy zero, with a blizzard of –40C blowing away outside.

Like the rest of the Marines, the press learned why ‘Logistics sucks’. Support company – the soft option – whose job it was to look after our coming and going to Norway, was a simple PR task but they failed miserably. (The offer of a drink would have heen a start).

I suppose it was this suppressed antagonism that contributed to the journalists’ mean mood. Why one of the Press corps threw a snowball at the MPs Land Rover outside the disco – just as the redcap happened to pop his head out …

“I’ll see your ID!” the policeman thundered, dripping snowdrops.

“Sorry mate,” the former Marine replied. “No ID. I’m civvie now.” His grin was very wide.

Bombing Out in the Andes

Research for White Viper by Terence Strong

My thriller WHITE VIPER has its origins in a research trip I made to the Greek island of Crete, while writing the previous book called Stalking Horse.

I arrived off-season in April and found that the tour company had given me an apartment next door to another lone male traveller. We had a drink together and immediately got on well.

I had met the ‘real life’ character on whom I was to base Kurt Mallory, a most extraordinary man with a most extraordinary story to tell. I picked up on some nuances and passing comments made by Kurt which may have been missed by the casual listener. Gradually, as trust was established between us, the truth gradually surfaced.

Only later I learned that Kurt’s holiday in Crete was to rest and recuperate after a harrowing undercover mission to Colombia. There, as part of a joint UK/US/Israeli hit team, he had single-handedly infiltrated a vicious British-manned cocaine production and distribution network linked to the former Medellin cartel.

He worked with the gang for several long weeks, having to witness intimidation and atrocities directed at the local population which he was helpless to stop, before his intelligence-gathering mission was complete.

Finally the hit team struck, wreaking a most terrible retribution and extracting details of a narcotics network that snaked all the way back to the British Isles. In the end, over thirty British nationals disappeared in the remote Andean cuchillos. No trace of the bodies has ever been found.

As Kurt himself told me somewhat graphically: ‘You survive in this game like the jaguar, by burying your shit behind you.’

The essential facts of WHITE VIPER are true. Most incredible of these is the existence of the organisation that has no name. An organisation dedicated to tracking down and destroying – by whatever means – those responsible for spreading the misery of narcotics addiction around the world. Reaching out to the untouchables who believe they are beyond the law.

And perhaps they are. But they are not beyond the cold hand of the organisation to which the real Kurt Mallory has devoted his life.

Little has been changed in this fictionalised account of Kurt’s own astounding origins, his life or personality. It is how you find him.

Never again will you look in the same way at that scruffy tramp, that vagrant, that vago pequeno as they say in South America.

Because, one day, he may be your only salvation.

A year later, after a month’s crash course in Spanish, I found myself in Colombia, retracing Kurt Mallory’s story.

“I’ve heard there’s a bomb at the air strip,” Hermando told us.

Already I had discovered that Hermando was very well-informed when it came to the activities of the local left-wing ELN guerrillas who controlled the surrounding countryside outside the remote Colombian town of Malaga in the Andean foothills.

The reason was simple. Bearded, bespectacled and gently mannered, he taught English at the local college and many of the guerrillas were his former pupils. And through ‘a friend of a friend’ he had already arranged safe-passage for me to the even more remote settlement of Concepion.

That was twenty kilometres farther into the unforgiving cuchillos where the real events which inspired WHlTE VIPER had taken place.

The truth was that, despite my deliberately unkempt appearance, my fair hair and blue eyes rather set me apart from your average Latino. And, to a penniless peasant guerrillero, all gringos were considered fair game for kidnap and ransom and I really didn’t fancy my wife having to re-mortgage the house in order to get me back. Added to which I wasn’t yet sure how highly my new publishers Heinemann valued me. How many pesos would their notoriously ‘hard-nosed’ Aussie MD, John Potter reckon a seasoned thriller writer like me was worth? Not as much as the guerrillas, I suspected.

I had already forged a letter of accreditation from the University of Southampton, passing myself off as a professor studying Indian cultures in the Andes, but that was for the benefit of bent-cops to go with a small back-hander. I doubted it would work on illiterate guerrillas.

(Of course, the forgery should have been unnecessary. Just before I’d left England I’d lectured on the art of thriller-writing to the university’s Writers Conference and assumed it would happily provide the documentation. It refused on the grounds that my showing such a letter to some gun-happy comisario in the upper reaches of the Orinoco might bring the university into disrepute!)

Anyway, Hermando’s promise that I could pass through guerrilla territory unmolested held good and now here he was again offering words of sound advice. Having endured the nine hour death-defying bus journey to Malaga from Bogota, along tortuous mountain mud tracks, passing through the cloud base in hour after hour of torrential rain, I’d decided to return by taking the little two-engined airliner off the shelf-like strip above the river canyon. My interpreter Luz – who charmingly combined flirtatious wit with a feisty determination to get me to wherever I wanted to go – and I were packing to catch the flight when Herrnando arrived to say his goodbyes and at the same time warn us that we weren’t going anywhere.‘We often get bomb threats, ‘ he explained. ‘They never come to anything, but it’s enough for the airline to cancel any flights. It’s in their insurance contract. Of course it’s just a rumour … ‘

Luz

We were now faced with the daunting prospect of a return journey by bus. It was awful enough for us to open the plastic bottle of whisky in search of solace. Then suddenly the phone rang. Luz had obviously made an impression on someone at the airline office at the strip. The flight had indeed been cancelled, but a little Police Cessna was taking off in five minutes. If we could make it, there were two seats for us.

Grabbing rucksack and bag, Luz and I bade farewell to Hermando, checked out and ran like crazy for the strip. We arrived just in time, the little eggshell-fragile single-engined aircraft already warming up. Squeezing into the back we joined the pilot and other three passengers. It was so cramped we couldn’t move and we were poked in the face as a bag was passed back to lighten the front weighting. The tiny machine began to move, bouncing along the strip towards the yawning abyss of the river canyon.

“Is the hatch shut properly?” the pilot called back and Luz translated, her eyes white and wide. I checked. It wasn’t. Too late now. I just grabbed the handle and held the hatch shut as though my life depended on it – which I suppose it did, really.

I then realised that the souvenir machete, strapped to the side of the rucksack on my lap, was pointed straight at my groin. Never mind a crash, just an emergency stop and I was done for now.

Then we were airborne, swooping out over the aching emptiness of the cuchillos, one of the most desolate and inhospitable landscapes on earth.

I think it was then that I realised I had done the two very things I’d promised myself I never would; fly in a single-engine aircraft in the Andes and never in the afternoon when the mountain thermals were at their most unpredictable. Nevertheless it seemed an appropriately dramatic end to my visit to the location of the true WHITE VIPER story. I would use that memorable and heart-stopping flight and the only slightly less hair-raising outward bus journey to good effect when I later came to write my fictional account.

Only I wasn’t finished yet. I’d already swum, unwittingly, with the piranhas in the Orinoco in the badlands of Venezuela, but unknown to me then, I had yet to be stranded in the notorious Chapare coca growing region of the Amazon at midnight and to be mistaken for a member of the DEA by the local narcos.

© TERENCE STRONG Bombing out in the Andes

A Walk on the Dark Side of Ulster

Research for Rogue Element by Terence Strong

“I’ve someone who would like to meet you. He read The Tick Tock Man and thought you gave the Loyalists a fair showing. He’s some things he’d like to tell you.”

I am a little surprised as the ‘fair showing’ had been very much warts-and-all. I’d interviewed people from both Sinn Fein and Loyalist camps and had tried to give the views of both sides fairly in my own fictional ‘secret peace talks’ which, unknown to me, pre-empted the real thing.

It turns out that the Loyalists were delighted that anyone should even bother to ask them. Film and TV tends to glamorise the Provisional IRA; many books do the same, although most thrillers concentrate on the British establishment’s fight against the Provos. Nobody asks the opinion of those who live in the province and consider themselves to be fighting for their homeland, their culture and their very existence.

Anyway, the call comes at a good moment. I am just wrapping up White Viper and dusting off a few ‘back-burner’ ideas, none of which I feel ready to run with. It’s best not to start writing until a story’s got you so fired-up you can scarcely wait to put pen to paper.

Intrigued, I arrange to meet ‘Michael’ at a hotel in the Midlands. It is one of those shabby but friendly places that cater for commercial travellers and is virtually deserted at weekends. I am let in by the Chinese proprietor who utters the immortal words, “Ah, key is li’lI bi’ sticky”, as he turned the lock. (For some reason the phrase sticks in my mind.)

Michael arrives a little later with his friend, whom he introduces as ‘Jim’. I’ve learned by now that those connected with outlawed Loyalist organisations always use false names when contact is made with outsiders. That name is changed for each outsider. So if in a year’s time a call came through asking for ‘Jim’, the man would know it was me or something to do with me.

‘Jim’ is a big, quiet Ulsterman with a soft accent and pleasant manner. We open a bottle of malt and sit around my rather tatty bedroom with the afternoon summer sun streaming in through the window.

And in this rather bizarre setting, an even more bizarre story begins to unfold.

‘Jim’ had been a teenager in Ulster when the latest troubles began in 1969. Like many youngsters who felt they should do something to combat the IRA, he flirted with various paramilitary groups who set themselves up to protect their own neighbourhoods from terrorist attacks.

He soon became disillusioned, realising that many of their number were little better than the Provos. Instead he became enthralled with an organisation called TARA. It preached restraint while British forces held the line against terrorism, but darkly forecast that the time would inevitably come when the situation degenerated into a total civil war that no one would be able to contain. A war that would spill over into the Irish Republic.

Therefore TARA should prepare itself as the province’s ‘resistance movement’ in readiness for the ultimate doomsday scenario.

It came as quite a shock to ‘Jim’ when he and other youngsters were encouraged to enlist in the Rhodesian Army to learn the art of weapons-handling and guerrilla warfare for real. But this was no fantasy. His air tickets were provided free …

Only later did he learn that TARA had been taken over and manipulated by the British Security Service, otherwise known as M15.

And, later, when the white Smith regime collapsed and many Rhodesians moved to South Africa, so the links with MI5 went with them. This co-operation was strengthened when it was discovered that the Provisional IRA had training camps in Mozambique, then a Marxist state, and that PIRA was actively assisting the ANC withbomb-making technology used for atrocities in South Africa. During all those years ‘Jim’had been working as an ‘agent of sympathy’ for MI5 using his contacts with Ulster to help them keep control of the Loyalist terror gangs which MI5 manipulated for its own purposes.

These are stunning revelations. Some confirming previous media speculation, others completely new.

This is a story that has to be told.

I arrange with ‘Jim’ to go down the ‘ratline’ in Northern Ireland. Contacts are made by ‘runners’ who will have face-to-face contact to make arrangements for me. No one uses the telephone or posts letters. Only later innocent, open-coded calls be made to confirm times and places. I am expected.

It is December and little do I know that the Provisionals have already decided that the ceasefire is to end. But when I land at Aldergrove the cruel illusion is still continuing. No apparent Special Branch presence and the airport security checkpoint stands abandoned. Car drivers are being mercilessly hounded by the RUC. Now with nothing better to do, the officers are anxious to keep their tallies up because mass redundancies arethreatened. On a happier note, Belfast bustles with pre-Christmas cheer.

People from all over the province and from the south are visiting the city for the first time in years. Fear has disappeared after nearly a quarter of a century. The streets are thronged with Saturday night revellers and the restaurants are filled to bursting. But my appointments are with people who know it will not last and who are preparing for when it inevitably comes to an end. People who keep to the shadows.

Yet my escort is hardly menacing. A stocky, middle-aged man in a cardigan and polyester tie from rural mid-Ulster. ‘George’ is affable and kindly, but deeply concerned at where the peace process is leading, when we meet at my hotel.

I soon learn that virtually everyone of Unionist persuasion, not only hard-line Loyalists, is convinced that the British are determined to ‘sell out’ to Dublin at the earliest opportunity. Most likely it will be done with the stealth and guile befitting ‘Perfidious Albion’ and its usual machiavellian ways.

‘George’ runs over a list of people he thinks might be able to help me research the book. No names, no pack drill, of course, but he will visit them personally and set things up.

We meet on several more occasions. I visit his remote home in rural mid-Ulster. We sit with his dog in the front parlour before the electric fire and drink tea while we talk.

He confirms how TARA was once a front for M15 and how the organisation was set up as a resistance movement. Although some members had links with the hardline UVF, most were respectable middle class folk from the rural areas, farmers, lawyers, accountants and even policemen amongst their number. The sort of people MI5 felt they could trust to stay their hand, unlike the mavericks in the Belfast gangs.

During the Ulster Workers’ Council Strike of 1974, MI5 had smuggled in a vast supply of arms, explosives and communications equipment from Belgium through Larne Docks. Those supplies had been distributed to secret caches around Northern Ireland.

M15’s trust in the members was to prove well-founded. It appears those weapons have never been used in any terrorist atrocity to this day. In fact, the organisation’s lack of action has led to most ordinary Ulster folk regarding Tara as a moribund joke as it still puts out pamphlets full of fighting talk.

But all that is about to change, says ‘George’ earnestly.

In the mid-80s, after the Anglo-Irish Agreement followed hard on the heels of the Brighton bombing, another separate group was formed. It was actually called Ulster Resistance (UR) and it, too, managed to arm itself with large shipments smuggled from South Africa.

But this time MI5 moved to intercept them. The Security Service had no control over UR and, besides, its own agenda had changed. By hook or by crook, there was now going to be a non-violent political settlement in Ireland.

Half the arms got through, because by now MI5 had alienated itself from most of its former allies in the Loyalist groups. New caches were set up and, again, those arms are yet to be used.

It is time for me to leave for an evening appointment. We step out under a clear, frosty December night, the house and garden surrounded by fields.

“Before this ceasefire,” ‘George’ tells me, “I would always keep an old car blocking the drive in case the Provos came for me. They’d have to come in on foot and the dog would always give a warning. This is a mixed area. A lot of Catholics are friends of mine. But you never know when they wave to you, they are not also making a note of your movements. Setting you up to be assassinated.”

It is a sobering and sinister thought. And just then there is a noise behind me in the field. Ceasefire or not, this man is a potential Provo target and I am standing right next to him. My heart stops. I spin round. The horse in the field neighs as it leans over the fence to see what is going on.

‘George’ gives a sympathetic smile. “That’s what it’s been like living here for the past twenty odd years. You never know when it’s going to happen to you.”

He indicates the hill, an inky outline against the starry sky. “Just over there is the nearest Catholic enclave. That’s the way they’ll come when the civil war starts.” There is no sound of doubt in his voice, just a deepsadness. “I’m afraid there will never be peace until they’re all driven out. Lock, stock and barrel. Because, you see, until that happens, we’ll never know which of them is the enemy.”

Our next rendezvous is at a public roadside car-park. We are to meet a Loyalist with a reputation for over thirty notches on his gun, who is to become my model for the fictional ‘Rattler’ in Rogue Element.

I am told that most of those killings have been at the behest of MI5 who provided the targeting information.

‘Rattler’ has never been caught because he always does his own reconnaissance and strikes at a different time and place to that agreed with the Security Service. They have never had the opportunity to stitch him up or sacrifice him as a scapegoat in any of their labyrinthine schemes.

But something has come up, and the crafty urban fox is now ‘on the gallop’. I’m told, “He sent his apologies.”

Instead, ‘George’ has set up someone else for me to meet. “He’s an important player … And a fan of yours.”

I really do worry about my fans sometimes.

The rendezvous is at another car-park, this time beside a lake. Dusk is settling and the bare winter trees are outlined against a blood red sunset. There are only half a dozen vehicles here, some empty, some with passengers inside.

I am driving a hired car. ‘George’ says, “Drive round slowly before you stop. I’ll see if I recognise anyone, or notice anything suspicious.”

My mouth goes dry and I obey. “Okay, pull in. Face the lake, but don’t park too close to the fence in case we need to get out in a hurry.”

I stop with the steering wheel on a full left-hand lock so we can drive straight off without reversing. It is an unnerving wait, getting darker, watching cars flash by on the road, one occasionally coming into the car-park, blinding us with its lights. Our friend? Or a Provo hit-squad? Or even a Det or SAS stake-out? It happens all the time over here and I don’t really know who I’m with or what they’ve done… or are planning to do.

At last ‘Freddy’ pulls in. We join him in his family saloon with fluffy dice dangling above the windscreen. A pleasant-featured, middle-aged man in a green waterproof jacket that is too bulky around the belly for his slim build.

I am inquisitive. “Are you tooled up?”

“Don’t ask.” A wry smile. “You can never be too careful.”

We chat about my books, especially those set in Africa. He loves Africa, has spent much time there. Like ‘Jim’, he was sent for training as a member of TARA by MI5. He confirms what ‘George’ has told me. But adds some more. “MI5 has no friends left amongst the Loyalists, except one who the Brits allows to peddle narcotics. It’s their plan to subdue the Protestant youth, dull their cutting edge.”

It sounds far-fetched, but ‘Freddy’ clearly believes it and I know enough about Northern Ireland to know that anything is possible.

He adds, “MI5 is no longer in control of TARA. It’s now joining forces with the Ulster Resistance to take the war to Dublin. There’II be a campaign of violence until the IRA declares a permanent ceasefire and the Republic drops its constitutional claims on the North.”

‘Freddy’ clearly means every word. Although it becomes equally clear that the Loyalist camp is very unclear about the timing of such a campaign. While the British Government is standing four square against terrorism and not yielding concessions, some factions would prefer to exercise restraint. Others feel that the campaign is both inevitable and essential anyway, so best to get on with it.

“And when that happens, it will degenerate into all-out Civil war,” ‘Freddy’ says emphatically. “If everything goes to s**t and the British Army can’t contain it, the Republic will send in its troops to protect the Catholic enclaves.” This sounds like crazy talk to me, but ‘Freddy’ is without doubt. “That’s what Dublin planned to do during the riots in 1969 – until the British established order.”

“Irish troops fighting British?” I ask, incredulous.

“Dublin didn’t reckon it would come to that. They’d go into the North in a blitzkrieg and seize the enclaves, on the assumption Britain wouldn’t have the stomach for a fight. And I’m sure they’re right. There’d be a standoff, the Americans would get involved, and we’d end up with UN troops on the streets of Belfast and Londonderry. And by that time the Loyalist community would have lost. That’s why the resistance movement must stand ready.”

“But the Republic didn’t intervene in ’69,” I point out.

A smile from ‘Freddy’. “No, they settled for setting up and training the Provisional IRA as a safer long-term bet. But those contingency military plans still stand, and the Irish Army has rehearsed them regularly every ten years or so. The last time was just before the Downing Street Declaration.

“Dublin dressed it up as border weapons searches. But you don’t really need artillery and armoured cars for those, do you?”

We discuss things I’d like to help complete my thriller. Like the exact battle plan of this Irish Army incursion and what about the peacetime disposition of their units? The sort of stuff’ Freddy’s resistance movement would have to know to carry out its plans. As good a test as any, I thought.

It’s dark now and eerie sitting in a car by the lake discussing such things. ‘Freddy’ needs to discuss something private, and I suspect deadly, with ‘George’ before he goes. “Leave it with me,” he says, “I’ll see that you get what you need.”

The next day I have another meeting with ‘a player’. I get my taxi to drop me off some distance from No 79 in the staunch Loyalist area street and walk the remaining distance to be sure I’m not followed.

As I approach, a car drives away from the house and no one answers the bell.

Probably a mix up on the time, I think. Or else he’s popped down the road for some cigs or a jar of coffee.

As I wait, I notice how nearly every house has Venetian blinds closed at the windows, so as not to offer a silhouette for any passing Provo gunman. Small, chilling detail we never think about over on the mainland.

Time passes and I hunch against the cold, sheltering behind the high hedge that separates the adjoining garden in the terraced row. I’m feeling and looking mean in my leather bomber-jacket, jeans and sneakers and glasses with dark Reactolite lenses.

Exactly how mean I don’t realise at the time. Any more than I realise I am being watched, either by a static covert observation post in someone’s loft or from a video car. I’ve been clocked, probably by the Det, the army’s under cover unit which is more generally referred to as 14 Int.

Behind the scenes, a major panic is probably going down, just because I can’t read my own handwriting. The man I’ve come to see lives at No 77, not 79. And for an hour I’ve been lurking next door to his house behind a hedge …

Who the hell is this new gunman on the block, Loyalist rival or Provo? Dark glasses in winter and no doubt a pistol concealed in his leather jacket. “No matching mug-shots known, boss …”

It is some nine months later, after a mysterious phone call from London, that I learn all this. But that’s another story that cannot be told.

In the meantime, however, a package arrives by safe hand. It is from ‘Freddy’. Inside is a complete assessment of the Irish Army’s order-of-battle, including locations of all units and a blow-by-blow breakdown of its plans to seize the North.

The IRA ceasefire finally ends and still there is no news of Loyalists taking the war to Dublin.

Then, three months after Rogue Element is delivered to my publishers, the following item appears in the Sunday Telegraph (9 February ’97):

“A new breakaway Loyalist group is threatening a violent campaign against the Irish government – until the IRA declares a permanent cease fire and Dublin drops its territorial claim to Northern Ireland.

“’The hard-line Loyalist Volunteer Force is believed to consist of around 500 activists with access to weapons which include rifles and explosives.”

Indeed, sometimes fiction can be truer, as well as stranger, than fact.

Me and My Car

An Article from the Sunday Times