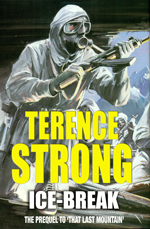

This fictional short story is based on a real-life incident and is a prequel to the thriller That Last Mountain. It was first published in Mayfair magazine.

This fictional short story is based on a real-life incident and is a prequel to the thriller That Last Mountain. It was first published in Mayfair magazine.

Click the book cover to download pdf, or read on:

ICE-BREAK

“I WANT a divorce.”

She said it like a spoiled child demands an ice-cream. Expecting to get a half-hearted reprimand, but also certain that she’d get her way in the end. And Joan had usually got her way; that had always been my mistake.

Uneasily I glanced around the pub. The festive decorations and tree in the corner just seemed to add salt to my emotional wounds. This wasn’t one of the regular haunts of my oppos from 22 Special Air Service Regiment, that’s why I chose it. But you couldn’t be too careful, and there was no way I wanted rumours doing the rounds in the mess.

I said: “Let’s give it more time.”

“We’ve had time,” Joan replied sourly. “Too much already.”

I looked at her carefully, as though seeing her for the first time. She’d changed, as we all do, but not for the better. The bland, cheerful face had been left behind with her teenage years, the once ready-smiling lips now permanently down-turned. Her eyes were full of hurt and resentment. Resentment that I wouldn’t make it easy for her to leave for the lover I knew she had.

Somewhere behind the bar an old-fashioned telephone rang noisily.

“Another month,” I said. I knew I was pleading. It was something I didn’t like doing. But Joan was all I had. Being an orphan, having someone close meant a lot. It was a fact of which she had reminded me on more than one occasion. “I’ve got Christmas leave coming up. We can spend it together. Go away somewhere. Get to understand each other.”

“And then away again without a word?” she asked pointedly.

“How long will it be this time? Six months? Nine? A year?”

I knew she was blaming ‘The Family’. But we both knew it was just an excuse. Like we both knew I could hardly deny I was away too much.

The barman leaned towards our table. “That your red MG outside?”

He must have read the instant concern on my face. Sometimes I thought that old roadster meant more to me than Joan. Perhaps it should have.

“Then you must be Mr Hunt,” he said. “Call for you.

I took the receiver over the bar. “Hello, Brian?” I recognised the voice instantly. Gabby Ash. The wife of our Mountain Troop commander, Mike Ash. Even as she spoke I found myself asking why the hell Joan couldn’t be more like Gabby Ash. I could forego the fair hair and those eyes of robin’s egg blue. But what wouldn’t I have given for her sympathy and understanding, and those ever smiling lips? At least that was how I felt when Gabby had looked at me when we’d last met.

“What is it, Gabby?”

“Thank God I’ve found you, I’ve been trying everywhere. Then I remembered this pub – There’s a call from the adjutant. Do you want to go to a party?”

“Christ,” I breathed. The code. “Where’s Mike?”

“Tanzania.”

Of course, planning a climb on bloody Kilimanjaro. God, didn’t he ever get enough of it? “Okay, thanks. ‘Bye.”

I picked up Joan’s coat. “Sorry, we’re going. There’s a flap on. I’ll drop you off on the way.”

She managed to look both angry and smug at the same time. “And our Christmas together?”

There was a flurry of activity at Stirling Lines, which had every home comfort and which every ‘old-timer’ loathed as a characterless red-brick university which, jokingly, only gave you qualifications to kill people.

Major Johnny Fraser was taking the briefing of the four troop sergeants. He was Counter-Revolutionary Warfare Wing – the anti-terrorist experts; we were Mountain Troop and our paths rarely crossed. So I knew someone had been caught with their pants down.

It was a miracle Fraser had been able to contact any of my men before they went on leave. Apparently they’d only found ‘BigJ oe’ Monk because his caravan had a puncture as he was towing it out of his drive. He should have been spitting mad, but you wouldn’t have thought so from the wide grin of tombstone teeth. So I knew this flap must be looking good.

“Glad you could make it, Sarn’t-Major,” Fraser said. “We’ve only mustered a half-deck. With Mike in Tanzania, looks like you draw the short straw. So, if you’re sitting comfortably …”

It was a rapid, clipped briefing delivered in the major’s usual calm Edinburgh brogue. A Soviet ‘trawler’, bristling with antennae, had put into the north Norwegian port of Hammerfest for emergency repairs after colliding with an ice-pack. The First Mate had jumped ship and offered himself up to the local police as a defector. Because of bad weather, it was not possible for an aircraft to fly the seaman south, so the local authorities had taken the precaution of moving him inland, away from the port, to avoid a diplomatic incident.

However, in transit, the car had evidently been forced off the road by a group of Soviet heavies. Favourite theory was a naval Spetsnaz special forces team. By the time the authorities realised something was amiss, the snatchers, with the defector and the local Norwegian police chief accompanying him, had got as far as Bǿrselv on Porsanger Fjord. There, five sets of footprints led across country from the abandoned car, heading south.

A local Norwegian Army unit had tracked the group to a remote hunting cabin in the taiga near the Swedish border. So far no word of the incident had reached the press, but it was only a matter of time. When it hit the fan it would present a major diplomatic problem.

The Norwegian Government had requested ‘technical assistance’ from 22 SAS. I knew what that meant; we all did.

It meant trouble. Fraser’s CRW Wing was stretched at the best of times and, with something evil brewing at a foreign embassy in London, he temporarily was ’embarrassed’ of manpower. We were the not unwilling answer to his prayer. Of course, we’d all done the training, but we were rusty. And that was not something it was wise to dwell on.

The briefing finished, I found the fourteen other members of our hastily-assembled force counting the spoils of their lightning raid on the Quartermaster. Arctic cam-whites, skis, ropes, crampons, ice-axes, packs – maybe a Mountain Troop wasn’t such a bad choice after all.

There was hardly time to load the kit into the Puma helicopter before it took off for RAF Lyneham in Wiltshire. The giant CI30 Hercules was waiting, its Allison turbo-props already turning impatiently.

Five hours of ear-splitting hell in its cavernous hold found us in northern Norway, and the first bit of good news that day. My old rival, jug-earred Sarn’t-Major ‘Dusty’ Miller of the Royal Marines Mountain and Arctic Warfare Training Cadre was waiting. Better than that were the BV snowcats he’d brought with him for our use. Immediately one was adopted as our operational base and comms centre.

The trusty tracked monsters made short work of drift-covered roads and the treacherous climb up through the tree-line to the site of the hunter’s cabin. And they appeared to thrive on the stinging sub-zero temperature that froze the skin on your face if you left your ski mask off for more than a few moments.

Whilst our HQ team established secure links with Oslo and Hereford, I made myself known to the local police-chief.

Whilst our HQ team established secure links with Oslo and Hereford, I made myself known to the local police-chief.

Gert Finn was a giant bear of a man, the impression enhanced by the thick fur coat and boots he wore. He had a tough, leathered face and hard I’ve-seen-it-all-before eyes. But this time he was totally out of his depth.

“Has any contact been made?”

He shook his head. “Not unless you count them shooting at us. There is no telephone, and I did not want to approach. You see the cabin is in the centre of a forest clearing some 200 metres in diameter. They have a clear view. My men would be sitting targets. Besides -“.

I sensed there was worse to come. “What?”

“A car registered to a Norwegian woman – a Vita Tilberg – has been found parked under the trees just off the track. She is not the owner of the cabin. We think maybe she is inside. An accomplice? A hostage?” He shrugged. “We do not know. Was she alone in the cabin? Is the owner also there? If so, why were they in the cabin? Who is she?”

I said: “Then the sooner we get in for a closer look the better.”

He shook his head. “Impossible. The snow is over two metres deep so you cannot move quickly. You will be seen.”

I kicked at the stuff. “There’s a way, Gert. There always is. ”

And this way was one hell of a slog. A hundred metres oft unnel, chipped and shoveled through the deep-frozen layers of old snow. I put ‘Big Joe’ Monk in charge of the first team; he was the sort of bloke who didn’t know the meaning of the word impossible. He was either thick or incredibly determined – or maybe both, as I’d jokingly told him many times before. Stripped naked beneath their water-proofs, the team would sweat buckets in their task and lose pounds of bodyweight before the job was done.

I dispersed the rest of my men as ‘stop-groups’ covering all angles of fire around the clearing.

Satisfied that all was going well, I returned for an update to the BV that was serving as our HQ.

Len Pope was pure Hampshire, a real country boy. A veteran of the Regiment in his late thirties, he was also the inseparable oppo and protagonist of Monk. The ‘unholy alliance’ of Monk and Pope.

“A report through from the GCHQ, boss,” Pope reported.

“Them and NSA have picked up HF transmissions from this area and responses from the Moscow region. One-off codes.”

That pretty much confirmed all our fears. This ‘First Mate’ of a Soviet’ trawler’must be highly-regarded for such a risky snatch to be made – under direct GRU control – when glasnost and perestroika was all the fashion. Funny, I mused, how everyone thought what a nice guy Gorbachev was when, behind the scenes, espionage activities had increased manifold.

“Is it true about the woman?” Pope asked tentatively.

“What?”

“That one of the Spetsnaz team in the cabin is a woman?”

“Jesus, Len, not that old chestnut.” The legendary ‘Volga Olga’. Ever since it had been learned that the elite Spets assassination teams sometimes included women, rumours of sightings in Norway were getting beyond a joke. “Whose idea was that?”

“Some bloke in Noggy security. He was just speculating.”

“Too much moonshine more like. Or your wishful thinking. Forget it.“

Still dwelling on the unlikely possibility of the lady’s existence, I sought out Gert Finn who was involved in an untypically heated exchange on the telephone with his superiors in Oslo. He was not a happy man.

“Impatient bastards,” he snarled at the handset. “Don’t they realise it takes time!

What can I tell them?”

I said: “That we need decisive action. It’s time to show our hand before Moscow sends over a team to pull them out. And we must establish direct communication.”

That pleased the police-chief. Fifteen minutes later he was doing his ‘You are surrounded’ routine over the bullhorn with great relish.

There was no response from the cabin, even when Finn told them that he was going to establish a field-telephone link. It was a moment of high-tension as Monk, in the uniform of a Norwegian policeman, waded through the snow, unravelling a land-line cable behind him. Nothing stirred at the cabin as he placed the field-set on the verandah and thankfully retraced his footsteps.

When the clearing was empty again, the door opened and a mitted hand reached out and pulled in the handset. The door closed again.

Finn made the call. It’s a strange experience, phoning up a hostage-taker for the first-time. He said: “Hello. How are you?”

Equally polite and incongruous was the reply, in perfect Norwegian. “We are fine. No one is hurt.”

The banter continued like this for a few minutes. Until an expert negotiator arrived, Finn would have to rely on the list of questions I’d given him. It was established that there would be no immediate danger to the hostages provided no one approached the cabin. There were provisions enough for one hot meal that night, and no one needed medicines or first-aid. The speaker refused to be drawn on the number of people in the cabin.

Finn said calmly: “Is it necessary to keep so many innocent hostages when our political masters will no doubt sort this out amicably?”

There was a short rasp of a laugh at the other end. Well, it had been worth a try. At least we were dealing with professionals. They sounded almost relaxed, so there was little danger of panic and the needless massacre of innocents by some jittery amateur.

At last Finn reached the bottom-line. “What exactly do you want?”

In response the line went dead. He looked at me and shrugged. “I guess they still wait instruction from Moscow.”

I could imagine the GRU mandarins running around like headless chickens at their Khodinka headquarters. I said: “I need another cabin, Gert, like this one. We have to practise – just in case.”

“No problem, Brian. There is one seven kilometres from here.”

“A psychologist from the MOD should be arrive soon. Meanwhile keep those bastards awake. There should be no rest for the wicked.”

I left him to it, found a space in one of Dusty Miller’s BVs, and bedded down in an Arctic feather bag. As I slept like a babe, the lads continued in relays to bore like ice-worms ever nearer the cabin. Finn phoned the Spets team at intervals throughout the night until they finally sussed him and pulled the plug. So he persuaded a Royal Marine to drive his noisy BV snowcat up and down, just to keep them on their toes.

Morning was little different from night. Almost as dark in the Arctic circle, and just as bloody cold. ‘Big Joe’ Monk had a brew on and played at being Mum with the oatmeal porridge and apple-flakes.

Len Pope arrived, dripping perspiration and wet snow. “We’re nearly through, boss.”

I could hardly believe it; no wonder he looked like a zombie. “Will it hold?”

“No problem. Thank God we hit soft stuff farther up the slope. Otherwise, we’d have been at it for days.”

Now we were in business. I gave Gert Finn the good news, and arranged for a ‘noise cover’ from manoeuvring BVs whilst I went up the hundred metre snow hole to inspect the target and supervise the insertion of the probe-mikes.

The tunnel finished at the rear of the cabin, beneath the snow line. It was possible to wriggle through into the open area under the floor which is traditionally used as a log store. The probes were worked in between the thick pine logs and tested that they were giving a clear reading.

But I decided against the probe camera. That meant hand drilling above the snowline to insert the fibre optic probe. As the Spets were taking it in turns to walk around the cabin to ensure that no one was up to the sort of tricks we were up to, that was a decidedly unhealthy proposition.

After all, I had back-up in the form of a thermal-imager the type of device firemen use to detect the heat-source of a human body in rubble.

By mid-morning a clear picture of the situation was developing. A sound scan with the probe-mikes indicated eight separate voices. Only one spoke solely in Russian, and he was quickly identified as the defecting ‘First Mate’. The four male Spets members (Pope would just have to swallow his disappointment) spoke Norwegian, except when talking to him. Finn identified the captured police-chief from Hammerfest, who was an old friend of his.

The cabin’s owner had also been identified: a successful middle-aged businessman whose wife thought he was on a solo elk-hunting expedition. The mysterious woman – surprise, surprise – was his secretary. Unfortunately they did not yet have photographs. However, this can hardly have been the sort of climax they had been hoping for in their cosy little love-nest.

Unwillingly I thought of Joan and how things should have been like that with us. Only I couldn’t afford a getaway love-nest.

The thermal-imager filled in the gaps, giving us vague shapes, but enough to register the general cabin layout and the position of the occupants.

From the verandah the front door led straight into the main room. There was a chemical lavatory closet in one front corner, a woodburning stove in the far left corner, and four trestle bunkbeds in the far right. A table and benches dominated the centre of the room. Simple stuff. But that very simplicity made it a tricky nut to crack. The only door and two windows were at the front, dominating the downhill view. There was just one other window in the right-hand wall, wooden shuttered; the two remaining walls were blind and made of solid Norwegian spruce.

Over a lunch of self-heating rations I held a ‘Chinese parliament’ with Len and ‘Big Joe’, going over every possibility of breaking the little wooden fortress. We’d tryout our ideas later on the identical cabin in the next valley.

Finn, too, felt more confident. The Spets had finally decided on their demands. A safe passage back to Soviet territory – with their ‘First Mate’ – in return for the release of the police-chief and the innocent hostage couple. Predictable enough.

Negotiations were calm, reasoned. Finn agreed to supply more provisions. It was looking as though we wouldn’t be needed after all.

Nevertheless we set out for our ‘rehearsals’ that afternoon, using all the data we had accumulated: cabin movement patterns from the mikes and the imager, rest periods, eating times, toilet routines. We whittled five options down to two, tested them both, and made a final choice. After ten dummy-run attempts we reckoned we’d succeeded six times without casualties. Not good. But not bad given the number of people in a confined space. We added a couple of refinements.

It was then I got the call. Finn’s voice was shaking. “God, Brian, it’s terrible! They’ve killed Oskar – the police-chief!”

“Calm down, Gert. Tell me what happened?” I demanded, hiding my own anxiety.

He took a deep breath. “One of their guards goes out to check up and collect wood from the store. He checks around the blind-side and falls into one of your snow tunnels!”

Oh, Christ.

“They are furious that they’ve been tricked. They shoot Oskar through the head and throw him onto the verandah. They demand a helicopter by morning or the girl gets it next. You understand?”

“I understand. How is the girl reacting?”

“I think your English word is hysterical. I am afraid she will do something foolish.”

I said: “Keep the lid on it, Gert. We’re on our way.”

“Oh-four-forty-nine,” agreed Finn, but he didn’t sound happy about it.

Never on the hour or a quarter. A golden rule. That’s the sort of time division that people set their alarms by. We synchronised our watches. Just over an hour to go.

Outside the oily warmth of the BV it was snowing thick and hard, a curtain of white petals blotting out the black velvet sky. It suited us.

The rear hatch of the snowcat opened. Major Johnny Fraser’s face was pinched with cold as he grinned. “Have I missed the party?”

I wasn’t surprised to see him. He was the sort of bloke who’d move heaven and earth to be up the sharp end with his ‘pilgrims’ whenever he could. “Just in time,” I answered, and added the magic words: “There’s a brew on.”

As he cupped the hot chocolate to warm his hands, he explained that the problems in London had been resolved. The CRW Group had its reserve back. “I’m afraid there’s no time for them to take over. Still happy to go ahead?”

“Sure, Boss,” I lied. I wasn’t happy about anything. Nevertheless I briefly ran over the plan. He seemed satisfied with it, and offered to take command of the HQ whilst I led the assault. You don’t turn down that sort of expertise.

H minus thirty.

H minus thirty.

In cam-whites we were virtually invisible as the eight man assault team approached the tunnel. Using a head-torch I led the way up the eighteen-inch rabbit hole. The dripping ice ceiling rubbed against my shoulders as I hauled myself along the slippery incline. In those conditions a hundred metres goes on forever. We reached the cabin with fifteen minutes in hand.

As the final preparations were made to the explosive charges, ‘Big Joe’ gave me the final sitrep. “The defector, the owner and his secretary are asleep on the bunks, along with one of the Spets. Two others are drinking coffee at the central table, and there’s one looking-out by the door.”

“Fine,” I said. “And is the field-telephone still beside him?”

“They haven’t moved it.”

Despite the eye-watering air temperature of minus forty, we were like toast as we waited, hearts thumping and adrenalin coursing. Weapons were checked. Browning pistols holstered. Heckler & Koch 9 mm MPS sub-machine guns loaded, safeties off, cocking-handles primed.

I said into the throat-mike of the Clansman PRC 349: “Minus two minutes.Charges into position, go.”

I break cover, ploughing up through the fresh powder like a snow mole, ‘Hockler’ out, its snout arcing defensively round to follow my line-of-sight. All clear.

Already two men are scrambling out of the snowpit, carrying the special shaped-charge of PE4 gauged to blast through the solid timber wall. My heart is thudding, sweat coursing down the small of my back. Two more men appear with the 1.2 x 0.6 metre frame-charge for the side window.

The digits flicker silently in the watch face on my wrist.

“Minus sixty seconds. Sunray, confirm no change of targets.”

The voice is tinny in the earpiece as Fraser comes in on the net. “Confirmed. Targets in position. No change.”

Thank Christ for that. No armed bastard caught short on the chemical lav as we go in. No nasty surprises. Suddenly the Kevlar body armour I am wearing beneath my smock seems to demand more trust than I am prepared to give it.

‘Big Joe’s’ voice is breathless.in my earpiece. “Charges in position.”

“Minus thirty. Standby, standby.” As I speak I join Joe’s team taking cover from the blast. At the side window I know Pope’s four-man patrol will be doing the same.

Twenty seconds. Standby,standby.

Joe’s face is only inches from my own. His eyes looking at me steadily through the smoked window of his respirator. An alien being. I’ve no idea what’s going through his mind.

Ten seconds. Standby, standby.

I stare at the figures on the watchface, mesmerised. Hoping time will stand still and we can all go home. My grip tightens on the ‘Hockler’.

Five, four, three, two –

Inside the cabin I hear the trill of the field-phone. Finn is calling the Spets team, a diversion, ensuring that one target at least is where we want him by the door.

I drop my hand in signal. And the whole world blasts apart with a flash as brilliant as fork-lightning. Huge spruce timbers vaporise, lethal jagged matchwood scything in all directions as the shock-wave reverberates around the mountains.

Despite the ear-defenders, my head is still ringing from the double explosion as rear wall and side windows are taken out simultaneously.

“GO, go go – !” I shout, already up and running towards the smouldering cavern even as the first stun-grenades are lobbed into the blackened void.

‘Big Joe’ and I are first into the smoke-filled interior lit by the angry fire of burning curtains. We open up together, the ‘Hocklers’ stammering out their rounds in deadly unison. The two Spetsnaz members at the table have been too stunned to move. Their weapons still lay before them, just inches from their fingertips.

We send the bodies spinning from their chairs.

Len Pope’s team are firing through the window, punching holes out of the front door as the man by the field-telephone takes a half magazine.

One to go. He’s there by my feet, decapitated by the blast. I move on through the stench of smoke to where the defector, the owner and the terrified girl should be in their bunks. And I pray to God they haven’t been hit by a stray round.

My heart sinks like a lift in a shaft. I can see their shapes beneath the blankets. There is no movement. I throw off the cover. I see the owner. He is dark-haired, and motionless. She is blonde, and quite, quite still beside him.

Emotion sticks in my throat as I reach out to touch her hair, and it comes away in my hand.

“Bastards!” I breathed as the realisation slowly dawned. I turned to the rest of the group. “Okay, lads, stand-down.”

‘Big Joe’ noticed my tone. “What is it, boss?”

I smiled sourly. “We’ve been had.”

Three minutes later Mike Ash, our Mountain Troop commander, came through the front-door.

“How was Kilimanjaro?” I asked, sarcastically.

He looked around at the shattered furniture and plastic dummies, weighing up the score. “Well done, Brian. Looks like a clean count.”

Finn entered next, looked at me sheepishly and shrugged. “Just doing my job,” was the best he could offer.

“You deserve a bloody Oscar, Gert,” I growled.

Johnny Fraser, head of CRW Wing, completed the party. “Next time we have the real thing, I’ll know where to come.” He glanced up at the loft. Of course, the stooges, who we had been monitoring on the sound and thermal scans, had to have been evacuated somewhere safe. “Better not forget to let our actors out.”

Suddenly I felt exhausted, drained. After the frantic activity of the past two days all I wanted to do was sleep. My eyelids would hardly keep open.

I know such ‘for-real’ exercises were necessary for us to keep a honed cutting edge, but it didn’t stop you hating them. Especially when I could have been with Joan, patching up my marriage. Or what was left of it.

Mike Ash said: “Gabby saw Joan yesterday. Asked to give you this.” He pulled an envelope from inside the smock of his cam-whites. I opened it later. The letter began: I want a divorce . . .